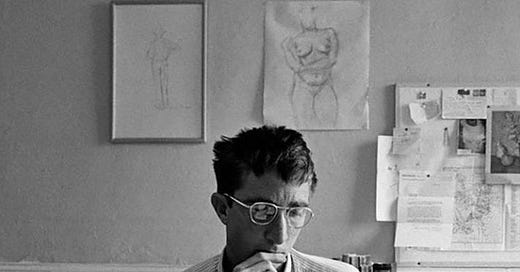

we’ve all been there, haven’t we? the conversation at a party, the dinner with friends, that seemingly harmless moment where we feel the creeping need to prove ourselves, to assert our intellectual worth. why does it matter so much to have others see us as smart, as capable, as someone with something of value to say? maybe it’s the way society has conditioned us, or perhaps it’s just human nature in its most vulnerable form, but the need to be seen as intelligent runs deep.

there’s a curious sort of paradox at play here: the more we seek validation, the more we expose our insecurities. and yet, the desire persists. it’s so baked into the fabric of modern life that it has become second nature, almost invisible to us, like the air we breathe. everywhere we turn, the pressure to be seen as intellectually capable is reflected back at us in the most subtle ways: in the pages of social media, in the way academic accolades are idolized, in the words we choose to share in conversations, and even in the ways we judge ourselves.

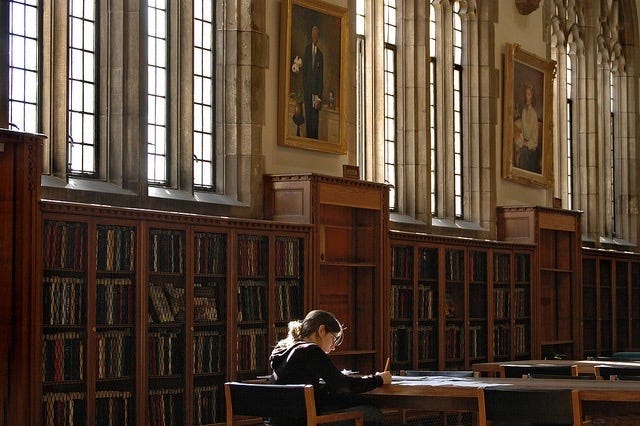

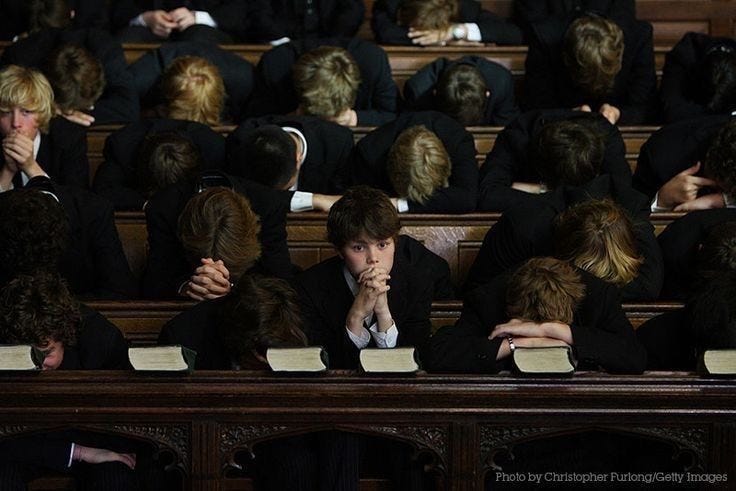

this need to prove our intelligence is not a new phenomenon. it’s deeply tied to our history, to the human condition itself. centuries ago, intellectualism was reserved for the elite. knowledge and education were the privileges of a small, powerful few—those who could access libraries, universities, and the great thinkers of the time. in a sense, knowledge was power. but over time, as education became more democratized, the idea of intellectualism morphed. it became something to be pursued by the masses, something to be flaunted, displayed, and celebrated.

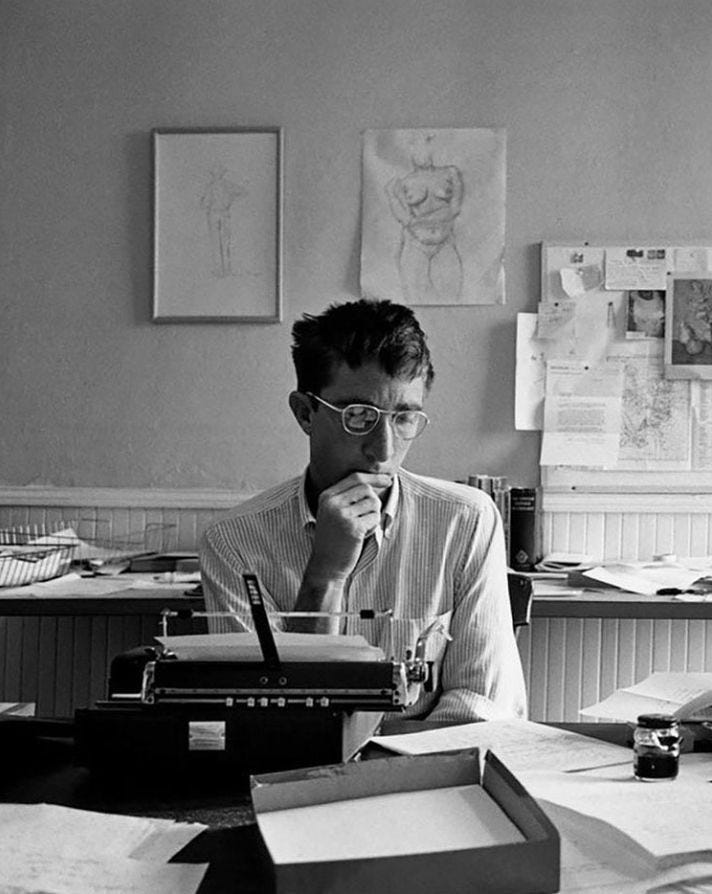

it wasn’t enough anymore just to have access to knowledge; you needed to show that you had it, that you were worthy of it. and so, the quest for validation began. but it’s not just about flaunting academic credentials or boasting about a hard-earned degree. it’s about creating a narrative around our intellect, to carve out an identity as someone who is well-read, well-informed, and equipped with the answers to life’s complex questions. in this world of endless information, the need to be seen as someone who knows everything becomes almost an obsession.

but what does this constant drive for validation say about us, psychologically? perhaps it’s rooted in something as old as human evolution: the need for acceptance, to fit in, to be seen as valuable. our ancestors lived in tight-knit tribes where being part of the collective was essential for survival. intelligence, then, was a tool for social standing, for leadership, for survival. those who could outthink or outsmart their peers were more likely to secure their place in the social order. it’s no wonder, then, that we still carry this instinct today—the desire to be seen as sharp, clever, and indispensable.

this psychology plays out in everyday interactions, from casual conversations to professional meetings. consider the social media landscape, where intellectual debates, book recommendations, and thought-provoking quotes from philosophers and writers are exchanged daily. it’s almost as if there’s an unspoken competition to showcase one’s mental prowess. the posts, the discussions, the comments—they all serve as proof of our intellectual status, evidence that we are worthy of admiration. but is this pursuit of visibility as an intellectual really just about the desire for validation? or is there something more insidious at play?

the philosopher michel foucault famously wrote about the concept of power/knowledge, suggesting that those who control knowledge control power. in today’s world, this is especially true. in a society driven by data and information, being perceived as someone who can decipher the complexities of the world grants us a certain power—both in how we navigate social spaces and in how we position ourselves in relation to others. when we share our intelligence, we are, in a way, asserting our place in the world, signaling that we belong to a certain echelon of thought. it’s less about the intrinsic value of intelligence itself and more about how it positions us in the social hierarchy.

but here’s where it gets tricky. in our modern world of constant connectivity, intellectualism has become a currency—a form of social capital that is traded in the open market of likes, retweets, and comments. it’s easy to think that sharing our knowledge is a way to connect with others, to show our understanding of the world. yet, in many ways, it’s also a performance. in a society where attention is fragmented and fleeting, sharing a brilliant insight or posing an intellectual question has become a way to capture and hold that attention, if only for a moment. the attention economy, as it is often called, has redefined what it means to be “smart.” it’s no longer enough to simply be knowledgeable; one must be able to express that knowledge in a way that resonates with others, that sparks interest, and, above all, that earns approval.

and therein lies the irony: the very act of seeking validation for our intelligence can undermine its value. in trying to prove how smart we are, we risk reducing our intellect to a mere tool for social gain, rather than something that is intrinsic, authentic, and valuable in itself. the constant chase for intellectual approval can become an exhausting, never-ending cycle, a performance we must perpetuate to remain relevant, to stay seen. it’s a form of self-objectification—transforming ourselves into an object to be evaluated by others, measured against an arbitrary standard of what “smart” looks like.

in a sense, our desire to be seen as intelligent reflects a deeper fear: the fear of being invisible, of being irrelevant. after all, intellect is often equated with purpose, with impact. if we are not seen as smart, does that mean we have no place in the world, no value to offer? perhaps this explains why we often feel the need to prove ourselves, to make our intellectual worth known, even when it is not asked for. we live in an era of profound existential uncertainty, where the line between being known and being forgotten is razor-thin. so, we speak louder, we tweet more often, we share our thoughts and opinions in the hope that someone, somewhere, will notice.

the social psychologist erik erikson once posited that one of the core human drives is the search for identity. in many ways, intellectualism has become an identity in itself—something we craft, curate, and showcase. it’s no longer enough to simply be smart; we must be seen as smart. we must perform it, display it, and ensure that others are aware of it. but in doing so, we risk losing touch with the true essence of what it means to be intelligent—to be curious, to be open-minded, to ask questions, rather than to always have the answers. intelligence should not be a badge to be worn, but a journey to be embraced. yet, in a world where identity is so often shaped by the need for validation, we can’t help but seek external acknowledgment for the inner truths we so desperately want to believe.

so, what’s the way forward? is there any hope of escaping this cycle, of truly embracing our intelligence without the need for external validation? perhaps the key lies in redefining our relationship with knowledge. rather than using intelligence as a currency to gain attention or approval, we can start to view it as something deeply personal, something that enriches our lives rather than defines them. the true measure of intellect is not in how much we know or how much we can show others that we know, but in our capacity for curiosity, our willingness to learn, and our ability to question ourselves as much as we question the world around us.

in the end, the pursuit of intellectual validation is a double-edged sword. while it may offer momentary satisfaction, it often leaves us yearning for something more: a sense of fulfillment, of purpose, that cannot be found in the fleeting approval of others. perhaps the greatest act of intellectual freedom we can commit to is to simply be smart, without needing anyone else to notice. to live and think authentically, without the burden of performance. after all, in the words of the poet w. h. auden, “a poet is, before anything else, a person who is trying to live a life of grace.” maybe that’s the secret—to live a life of intellectual grace, unburdened by the need for validation.

I’ve definitely been in those moments... dinner with friends, casual chats...where I catch myself trying to sound smart just to feel seen. It’s subtle, but it’s there. That weird tension between wanting to be authentic and wanting to be impressive.

Lately I’ve been trying to unlearn that. To enjoy learning and curiosity without turning it into some kind of performance. Feels way better to just be in the moment, without trying to prove anything.

I think real sophistication comes from that quiet confidence, just knowing who you are and not needing to explain it all the time

Part of seeking validation for intellect or knowledge is not about reaching out to the public masses. There's also an aspect of seeking validation from our closer connections, for whom it is not about clout or standing. Sometimes, we need to show that we have 'done the work' and that we are engaged in the issues that matter. Virtue signaling is sometimes necessary, not to impress, but to earn our space in sensitive communities. It is important to understand issues (queer and trans rights, systemic racism and sexism, intersectionality) and we have to be able to demonstrate that understanding; not to brag, but to be (and be seen as) a safe and contributing member of whatever community.